Is anti-Semitism irrational? It is certainly a malevolent and ultimately murderous ideology but saying it is irrational it not quite the same thing.

The recent outburst of feverish anti-Semitic violence in Amsterdam raises the question once again. How can such an outburst of visceral anti-Jewish hatred be explained? Or is it perhaps beyond any kind of logical explanation?

In its strongest form the claim that it is irrational casts anti-Semitism as a kind of psychosis. From such a perspective it is a madness that grips its adherents for no apparent reason.

But this pure form of the irrationality argument cannot explain why anti-Semitism is strong at times and weak at others. For example, it was a far greater force in Nazi Germany than in contemporary Britain. Nor can it explain why some people are drawn to anti-Semitism while others are not.

On the other hand, it is difficult to maintain that anti-Semitism is entirely rational. The Holocaust, most notably, seems like a model of irrationality. Even leaving aside any moral considerations – which should of course be paramount – it is hard to see who benefitted from the slaughter of six million Jews. From that perspective it is easy to argue that it is beyond rational explanation. An act of barbarism that defies human comprehension.

Perhaps the best place to start answering the question is to look at how some key authority figures have discussed it. It is notable in that respect that nowadays they tend to lean towards the claim that anti-Semitism is irrational.

Take Deborah Lipstadt, a respected historian of the Holocaust and special anti-Semitism envoy for the Biden administration. In a testimony in 2020 she argued unequivocally – as she has elsewhere – that anti-Semitism is irrational. She stated that: “There is no easy solution to prejudice because it is an irrational sentiment. Prejudice: the etymology of the word itself is testimony to its irrationality: to pre-judge, to decide what a person’s qualities are long before meeting the person him or herself.”

This approach is problematic for two reasons. First, it is questionable that anti-Semitism is just a prejudice. I have argued elsewhere in relation to Lipstadt that it is much more than that. It is also not possible to understand the nature of anti-Semitism simply by consulting a dictionary. It demands a proper investigation of the forms it takes.

Germany’s anti-Semitism commissioner is another important institutional force dedicated to opposing anti-Semitism. In the official view of the organisation as stated on its website: “There is no rational basis or cause for antisemitism; any alleged reason for it is irrational and false.” Although it recognises a degree of complexity in understanding anti-Semitism it concludes that: “its basic structure is always the same: every form of hatred towards Jews involves victim-blaming and treating them as a collective entity.” This is essentially a variation of the argument that anti-Semitism is a form of scapegoating.

In this context it would be remiss not to mention the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism, problematic though it is, as that has become the standard reference point on the subject. In this context it is notable that it avoids delving into the question of rationality. Instead it limits itself to outlining particular manifestations of anti-Semitism.

There are countless other examples but the idea of anti-Semitism as an irrational hatred is common in both academia and the popular debate. However, most of the time it is either asserted as true or the case is argued superficially.

One notable exception was Gavin Langmuir (1924-2005), a medieval historian specialising in the Jewish question. In his Toward A Definition of Antisemitism (1996) he made a useful distinction between what he called xenophobic stereotypes and chimerical stereotypes.

Xenophobic stereotypes have a kernel of truth to them. In relation to the Jews this could include the notion that they killed Jesus. That is because Jews did acknowledge that Jesus should have been killed as a heretic against their religion. That does not mean Langmuir was endorsing hatred based on the stereotype, he certainly was not, but he argues the notion did not emerge out of thin air.

In contrast, chimerical stereotypes have no rational basis. In relation to the Jews that could include the blood libel: the claim that Jews ritually kill non-Jewish children for their blood. Such claims are not based on anything anyone had observed. They are instead, in Langmuir’s view, a case of imaginary monsters conjured up by psychologically troubled people.

The problem with all these takes is that they focus too narrowly on Jews. That might seem a strange thing to say but it is wrong to see anti-Semitism as simply a prejudice, a form of discrimination or scapegoating. Typically anti-Semitism, at least in its most developed forms, links Jews to a broader conception of evil.

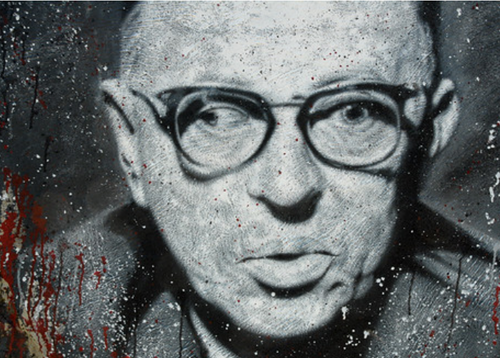

Different writers recognise this in different ways. For example, Jean-Paul Sartre, France’s most famous existentialist philosopher, wrote in Anti-Semite and Jew that: “Anti-Semitism is thus seen to be at bottom a form of Manichaeism. It explains the course of the world by the struggle of the principle of Good with the principle of Evil. Between these two principles no reconciliation is conceivable; one of them must triumph and the other be annihilated” (p40-41).

Indeed those who define anti-Semitism as irrational themselves often recognise a link to the notion of evil. According to the German Antisemitism Commissioner website: “In antisemitic thought, ‘the Jews’ often represent the abstract nature and values of the modern, globalised world. This is how antisemitism comes to terms with modernism and enlightenment: by reducing the complexity of modern society to a simple model in which powerful Jews secretly pull the strings and control the economy, the media and/or political institutions. In this way, antisemitism also serves as a way to understand the world and often appears in connection with conspiracy theories.” However, it immediately goes on to play down the significance of this insight with the point that the nature of victim blaming is always the same.

David Nirenberg, an American intellectual historian, tries to get round some of these problems by distinguishing between anti-Semitism and anti-Judaism. In his magisterial study on Anti-Judaism he draws on a controversial essay by Karl Marx to argue that: “the ‘Jewish question’ is as much about the basic tools and concepts through which individuals in a society relate to the world and to each other, as it is about the presence of ‘real’ Judaism and living Jews in society” (p3). In contrast he says that the term anti-Semitism “captures only a small portion, historically and conceptually, of what this book is about” (p3).

It is questionable whether Nirenberg’s terminology resolves some of the key intellectual problems. For one thing the term “anti-Judaism” is used by others in different ways. But the insight is important. Discussion which is apparently specifically about Jews is often really only explicable in relation to a broader conception of society.

Of course this point raises additional problems. In particular why is it the Jews specifically who are so often used as a way of thinking about conceptions of evil? As I have written elsewhere on this this these have included linking Jews to the supposed malevolent spirits of capitalism, communism, modernity and western civilisation.

The important point here is that there is a rationale behind anti-Semitism but it cannot be understood by simply focusing on the Jews themselves. It might be over-stating the case to describe anti-Semitism as rational but those who describe it as irrational tend to understand it in overly narrow terms.

PHOTO: "Jean-Paul Sartre, painted portrait - DDC_7520.jpg" by Abode of Chaos is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The aftermath of the 7 October Hamas pogrom in Israel has made the rethinking of anti-Semitism a more urgent task than ever. Both the extent and character of anti-Semitism is changing. Tragically the open expression of anti-Semitic views is once again becoming respectable. It has also become clearer than ever that anti-Semitism is no longer largely confined to the far right. Woke anti-Semitism and Islamism have also become significant forces.

Under these circumstances I am keen not only to maintain this site but to extend its impact. That means raising funds.

The Radicalism of fools has three subscription levels: Free, Premium and Patron.

Free subscribers will receive all the articles on the site and links to pieces I have written for other publications. Anyone can sign up for free.

Premium subscribers will receive all the benefits available to free subscribers plus my Quarterly Report on Anti-Semitism. They will also receive a signed copy of my Letter on Liberty on Rethinking Anti-Semitism and access to an invitee-only Radicalism

of fools Facebook group. These are available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £100 or a monthly fee of £10 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

Patron subscribers will receive the benefits of Premium subscribers plus a one-to-one meeting with Daniel. This can either be face-to-face if in London or online. This is available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £250 or a monthly fee of £25 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

You can sign up to either of the paid levels with any credit or debit card. Just click on the “subscribe now” button below to see the available options for subscribing.

You can of course unsubscribe at any time from any of these subscriptions by clicking “unsubscribe” at the foot of each email.

If you have any comments or questions please contact me at daniel@radicalismoffools.com.