How could Germany, a country dedicated to repudiating its Nazi past, end up spending millons of euros sponsoring an exhibition that included blatantly anti-Semitic images? To compound the embarrassment still further, Germany’s president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, opened the exhibition and chancellor Olaf Scholz was scheduled to visit.

This is the quandary that has haunted German leaders since the opening of the Documenta Fifteen international art exhibition in the city of Kassel in mid-June. The high-profile contemporary art event, which has taken place every five years since 1955, involved over 1,500 artists this year. And the curation had been outsourced to an Indonesian art collective, called ‘ruangrupa’, and involved many groups from the ‘global South’.

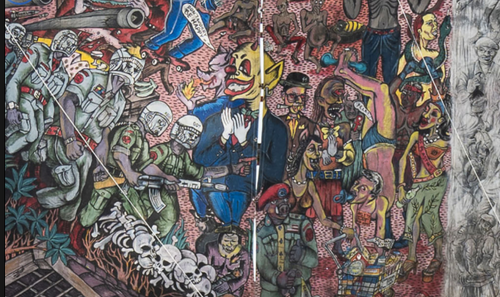

There should be no doubt about the anti-Semitic nature of some of the art itself. Certain works would not look out of place in Nazi Germany. There is no hyberbole here. There was an exhibit called People’s Justice by Taring Padi, another Indonesian collective, originally produced in 2002. It included two particularly vile images. One showed a man with side-locks and fangs, wearing a bowler hat with a Nazi SS emblem on the front. The other showed a soldier with a pig’s head and a helmet with ‘Mossad’ (Israel’s external intelligence service) written on it. After the furore, the exhibit was first covered up and later removed.

There were official apologies made for the error but they were distinctly half-hearted. For example, Sabine Schormann, the director of the exhibition, wrote in the regional newspaper, hna, that the Covid-19 pandemic made it difficult to prepare properly. But given that the artwork was first created 20 years ago, and that there had been controversy in the six months leading up to its opening, this is hardly plausible. To make matters worse, she implied that the key problem was the hurt feelings of Jews and Germans rather than the objective anti-Semitism of the exhibit.

The Taring Padi collective took a similar view to Schormann. In a statement released by Documenta, Taring Padi stated: ‘We deeply regret the extent to which the image of our work People’s Justice has offended so many people. We apologise to all viewers and the team of Documenta Fifteen, the public in Germany and especially the Jewish community. We have learned from our mistake, and recognise now that our imagery has taken on a specific meaning in the historic context of Germany.’ In other words, the murderous outlook of anti-Semitism itself was not the problem – rather, it was the delicate sensitivities of Germans and particularly Jews.

People’s Justice was not the only anti-Semitic exhibit. A work by Mohammed Al Hawajri, a Palestinian artist, also drew an equivalence between Nazis and Jews. Gaza-Guernica depicts Israel’s operations against Hamas-controlled Gaza as comparable to the German Luftwaffe’s targeted destruction of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War.

Then there is the fact that many of the ruangrupa organisers have publicly supported the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel. Although this movement presents itself as working to end ‘Israel’s oppression of Palestinians’, it regularly ends up demanding boycotts of individual Israeli artists. In this context, it is notable that there was not one Israeli among the more than 1,500 artists who exhibited, despite there being no shortage of Israeli contemporary artists.

This all raises the question of how anti-Semitism could have such a significant presence in a high-profile and publicly funded art exhibition. That is particularly poignant in contemporary Germany, which explicitly defines itself in opposition to its Nazi past.

It is certainly not the case that the current generation of German politicians are developing Nazi sympathies. President Steinmeier’s opening speech to the exhibition included several references to the horrors of anti-Semitism. And chancellor Scholz pulled out of a planned visit once the scale of the scandal became apparent.

But if anything, these actions deepen the quandary rather than dispel it. On an official level, Germany remains deeply opposed to anti-Semitism, no doubt genuinely in most cases, yet it has somehow ended up facilitating it.

Nor can Germany’s actions be explained by a principled attachment to artistic freedom. It would be possible to argue that the anti-Semitic character of the images should be acknowledged but, on the grounds of free expression, they should still be exhibited. But that was not the case here. Once the anti-Semitic character of the People’s Justice exhibit was belatedly recognised, it was quickly covered up and then taken down. Somehow, the German political class seemed to have bungled its way into facilitating such an exhibition without realising what the consequences could be.

The scandal is essentially the result of a clash between Germany’s postwar commitment to banishing its Nazi past and an emerging attachment to identity politics. Although both viewpoints have their problems, it is the new outlook that is opening the way for the re-emergence of anti-Semitism in a modified form.

When the Federal Republic of Germany was founded in 1949, in the dark shadow of the Second World War, it defined itself in direct opposition to its Nazi predecessor. It was to be a free and democratic state as opposed to its murderous and dictatorial forerunner. It also understood that it had to oppose anti-Semitism, whereas the Nazi regime of course took anti-Semitism to murderous conclusions.

To be sure, there are problems with the way the federal republic is constituted. Its elaborate system of political checks and balances acts as a check on popular sovereignty. And its commitment to tackling anti-Semitism is to a large extent instrumental: it was recognised as essential to rebuilding Germany’s postwar legitimacy, rather than being a selfless act. Nevertheless, the current generation of leading German politicians is generally horrified at the spectre of anti-Semitism.

But Jew-hatred is coming back not primarily in its old, far-right form, but rather in the new guise of identity politics. The old Nazi anti-Semitism could often be characterised as the ‘socialism of fools’, with Jews blamed for the huge dislocations often caused by capitalism. In contrast, the new anti-Semitism more often appears as the ‘anti-imperialism of fools’, with Israel’s supposed immense power, and that of Jews more generally, blamed for many of the world’s ills. This goes way beyond any balanced criticism of Israel to present the Jewish state as a malign influence endangering the whole world.

In contemporary Germany there is no doubt some sympathy for the latter view. That helps explain why the curating of the Documenta exhibition was outsourced to the ruangrupa collective. Despite the way it is generally discussed, it is more of a political organisation than an artistic one. As a sympathetic profile of ruangrupa in the New York Times magazine has noted: ‘To describe ruangrupa as an “artists” collective’ is a well-established shorthand but perhaps a misleading one. Not every ruangrupan is a conventional artist; one worked as a journalist, another trained as an ecologist, a third is an academic.’ It is probably better seen as an agitprop outfit which seized the opportunity to use the largesse provided by the German authorities to propagate its political outlook.

Ruangrupa’s approach probably makes for poor art, but it certainly leads to lousy politics. Its supporters would no doubt argue that they are siding with the world’s oppressed people against the evils of colonialism and racism. But this crude approach does not advance the cause of freedom for people in the world’s poorer countries. Instead, it has the unintended consequence of promoting other forms of bigotry.

This identitarian outlook is helping to create the basis for a new form of anti-Semitism in Germany. In the name of celebrating diversity, it is constructing a new hierarchy of victimhood, in which Jews are often seen as being to blame for the world’s problems. This really is the anti-imperialism of fools, rather than having anything to do with self-determination or freedom.

This article first appeared in spiked-online on 2 July.

PS: 7 July. Novo, a German online publication, has published a German language version of this article.