Maurice Samuel’s biography of Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935), a French army officer accused of treason, is an important contribution to understanding the rise of modern anti-Semitism. The broader points are woven into the gripping story of a scandal which took France to the brink of civil war from 1894-1906.

Although there is a huge literature on the Dreyfus affair surprisingly little of it focuses on the central role played by anti-Semitism in almost every aspect. Maurice Samuels, a professor of French at Yale and the director of the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism, succeeds in his goal of redressing the balance. He argues convincingly that hostility to Jews was the prime motivating force for those who opposed Dreyfus. It was not simply, as many have argued, an incidental detail in a universal story of injustice.

Samuels shows that the visceral hostility to Jews characteristic of most anti-Dreyfusards was far more than prejudice or mere hatred. From the 1880s onwards Jews unwittingly became caught up in a conflict between modernisers who wanted to transform France and reactionaries who opposed change. Jews somehow became symbolic of the broader shift in French society towards modernity. Anti-Semitism became a ‘cultural code’ – a shorthand – for those opposed to modernisation.

Samuels reveals this insight through recounting Dreyfus’s solitary fight for justice and the parallel public furore around his case. Indeed Dreyfus was not even aware of the commotion for the first few years as he was kept in isolation.

Dreyfus was on the face of it an unlikely figure to be accused of treason or to become the centre of a scandal related to anti-Semitism. In Samuel’s account he was an ardent French patriot and deeply shy. He was born in Alsace, a region of northeast France bordering Germany, into a wealthy Jewish family. Although his family were not devout, and they were well integrated into French society, they maintained their Jewish identity by attending synagogue.

In 1875, at the age of 16, Dreyfus resolved to enter the École Polytechnique, an elite university focused on engineering. He hoped this move in turn would provide the basis for him to become an army officer. After joining the army in 1880 as an artillery officer he then served in the cavalry. In 1893 he was appointed to the general staff as an intern with the hope that it would become a permanent position.

The following year he was arrested on charges of treason. French intelligence had discovered a document which suggested a senior officer was spying for Germany and, despite weak evidence, blamed Dreyfus. In December 1894 he was found guilty in just three days in a court that was closed to the public.

Early the following year he was shipped to Devil’s Island off the coast of French Guiana, in South America. There Dreyfus was forced to live in solitary confinement for several years, with meagre rations, in conditions of extreme cold and heat.

In 1899 he was allowed to return to France after his verdict was overturned but that was far from the end of the affair. He had to face a second court martial. That eventually decided against Dreyfus with the court finding him guilty by a vote of five to two but with “extenuating circumstances”. It was not clear what this term could mean in relation to treason. Nevertheless, Dreyfus was sentenced to another 10 years in detention.

However, in the face of concerted international pressure at home and abroad, the government quickly decided to offer him a pardon. This did not amount to a full rehabilitation but it enabled him to leave detention and live with his family.

Eventually, on 12 July 1906, after years more litigation, the court reached a final verdict. Dreyfus was completely exonerated. It was acknowledged that the military judges who originally tried him had made a monstrous judicial error.

While Dreyfus was engaged in his battle with the courts and in confinement the outside world was sharply divided over his affair. The reactionary element in French society was vehemently hostile to both Jews and modernisation. Indeed it struggled to distinguish between the two. Meanwhile, those in favour of modernisation were generally sympathetic to Dreyfus.

The most famous figure on the pro-Dreyfus side was Émile Zola, one of the country’s best known literary figures. In 1898 he famously wrote an open letter in defence of Dreyfus entitled J’Accuse…! ( I Accuse…!). Other prominent figures on the Dreyfusard side were two future prime ministers: Georges Clemenceau and Léon Blum.

Perhaps the most prominent figure on the anti-Dreyfusard side was Édouard Drumont (1844-1917). He was a journalist and author who ran La Libre Parole (The Free Speech), a mass circulation anti-Semitic newspaper, before entering politics. Samuels notes that he combined the socialist antipathy to Jewish bankers with the right-wing hostility of ultraroyalists and fundamentalist Catholics. Added to the mix was a dose of the latest racial theorising.

The left was divided on the question. Jean Jaurès, leader of the more moderate Socialists, at first ignored it on the grounds that it did not concern the working class. But eventually, in 1898, he rallied to the side of Dreyfus as he concluded that every citizen had the right to protection under the law. Jules Guesde, a more radical socialist leader, kept his distance from Dreyfus because the accused was a member of the capitalist class.

Underlying the Dreyfus scandal was a fundamental division in French society which had begun to emerge a century early. France was the European country most open to Jews and also arguably the country where modern anti-Semitism first took shape.

France was the first European country to grant Jews full civil rights. In 1789 the Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen declared that all men were born in equal rights. The was followed up by two decrees granting Jews rights as full and equal citizens. The first applied to Sephardim (Jews of Spanish origin) was made in 1790 and one for Ashkenazim (Jews of central European origin) in 1791. (Although women were not granted the right to vote in France until 1944).

Samuels goes from there to argue that the emergence of modern anti-Semitism was a reaction against emancipation. Anti-Semitic movements were opposed to the granting of full civil rights to the Jews.

My only criticism of the book is that it could perhaps have gone further in developing this argument. As I have previously argued, the emergence of the Enlightenment ideal of equality was, paradoxically, a pre-condition for the establishment of racial thinking. The idea of race emerged as an attempt to explain the persistence of inequality despite the widely professed attachment to equality. In the case of Jews the anti-Semites argued they were incapable of truly fitting into French society despite the revolution’s attachment to emancipation. They saw attempts to modernise society, including the inclusion of the Jews, as undermining the traditional essence of France.

But perhaps exploring the emergence of anti-Semitism as a form of racial thinking would have taken the book too far into theoretical territory. Overall the book admirably achieves its goal by providing an engaging biography of Alfred Dreyfus in the context of France’s ambivalence about Jews and modernity.

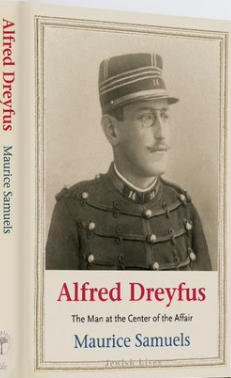

Maurice Samuels Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair . Yale University Press. Part of the Jewish Lives serios of biographies

Further reading from the Radicalism of fools. On How Jews came to symbolise modernity.

The aftermath of the 7 October Hamas pogrom in Israel has made the rethinking of anti-Semitism a more urgent task than ever. Both the extent and character of anti-Semitism is changing. Tragically the open expression of anti-Semitic views is once again becoming respectable. It has also become clearer than ever that anti-Semitism is no longer largely confined to the far right. Woke anti-Semitism and Islamism have also become significant forces.

Under these circumstances I am keen not only to maintain this site but to extend its impact. That means raising funds.

The Radicalism of fools has three subscription levels: Free, Premium and Patron.

Free subscribers will receive all the articles on the site and links to pieces I have written for other publications. Anyone can sign up for free.

Premium subscribers will receive all the benefits available to free subscribers plus my Quarterly Report on Anti-Semitism. They will also receive a signed copy of my Letter on Liberty on Rethinking Anti-Semitism and access to an invitee-only Radicalism

of fools Facebook group. These are available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £100 or a monthly fee of £10 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

Patron subscribers will receive the benefits of Premium subscribers plus a one-to-one meeting with Daniel. This can either be face-to-face if in London or online. This is available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £250 or a monthly fee of £25 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

You can sign up to either of the paid levels with any credit or debit card. Just click on the “subscribe now” button below to see the available options for subscribing.

You can of course unsubscribe at any time from any of these subscriptions by clicking “unsubscribe” at the foot of each email.

If you have any comments or questions please contact me at daniel@radicalismoffools.com.